Storage

This chapter is all about storage. We will start with a discussion of the main canonical types of storage, then move into how storage is typically managed in a database. We will explore the page abstraction and see how best to leverage it to minimize the amount of wasted or unnecessary computation.

Storage Types

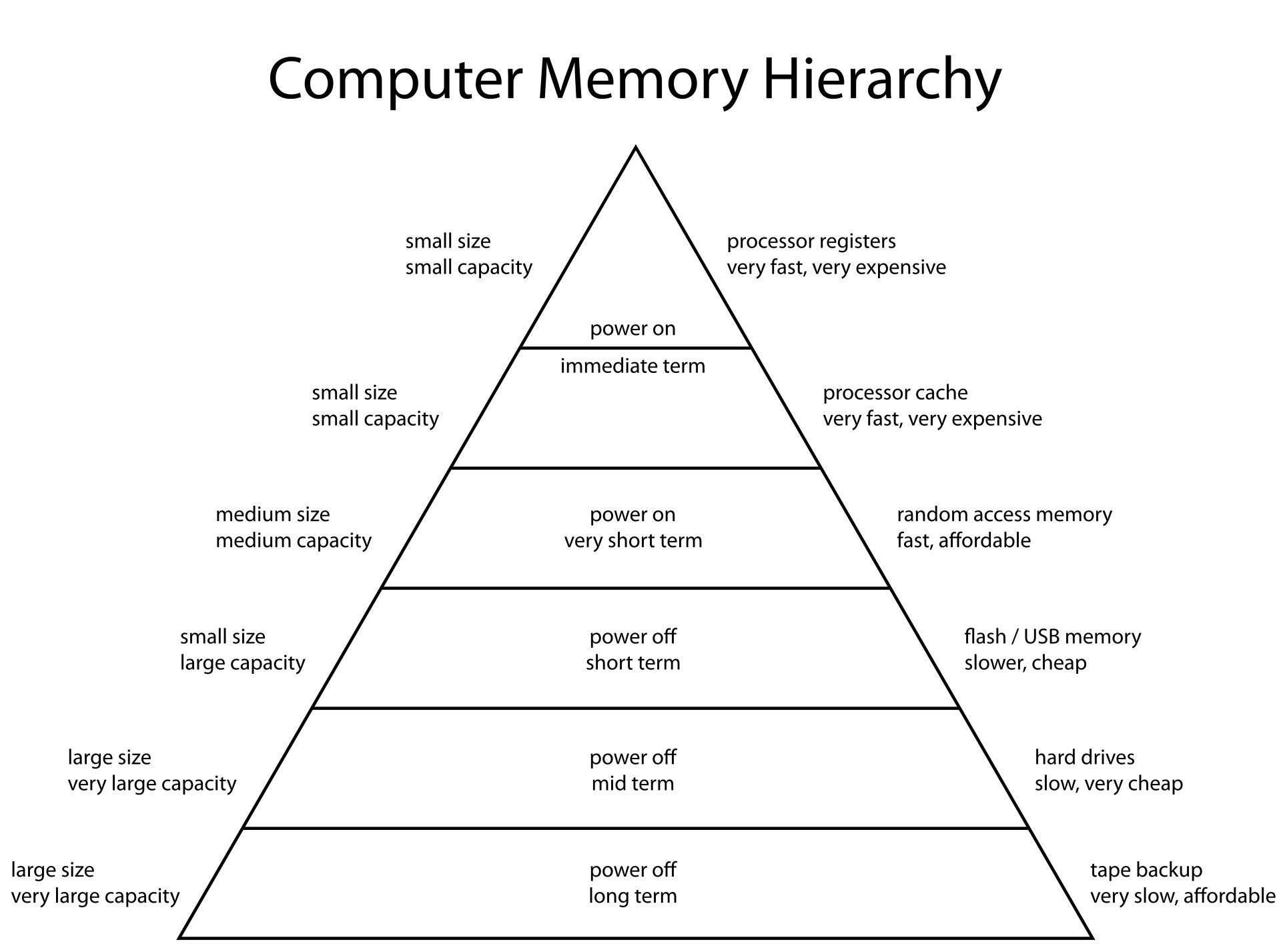

Storage is not created equally. There are storage media that are blazingly fast and cripplingly expensive, and there are those that are cripplingly slow but empoweringly cheap. For the most part, storage has gotten cheaper over time, but physical limitations will always mean we cannot deck out our setup with only the fastest memory.

Storage types differ in a few important comparable fields beyond price and speed:

- Will this data persist if power is lost?

- How long can I use this storage method before it breaks?

- What is the best way to read or write from this data?

Let's go through the storage hierarchy from cheapest and slowest to priciest and fastest, comparing on these metrics.

Backup Storage

At the bottom of the barrel we find magnetic tape storage. Magnetic tape storage essentially works by writing bits onto a special tape using magnets. It is dirt cheap and lasts forever, but incredibly tedious to work with. For one, all reads and writes must be done sequentially; there isn't a notion of a random read. As a result, they are incredibly slow and should only be used for backups or archival data.

Nonvolatile Storage

The first consequential category of storage is nonvolatile storage, otherwise referred to as disk. Disk differs from memory in that data stored on disk will persist even if power is lost to the system. It is much slower to read and write to disk, and we cannot operate on disk data directly; rather, we must pull it into memory or into registers and operate on it that way (this is a direct consequence of the Von Neumann computer architecture; other architectures could be conceived, but virtually all modern computers abide by this rule).

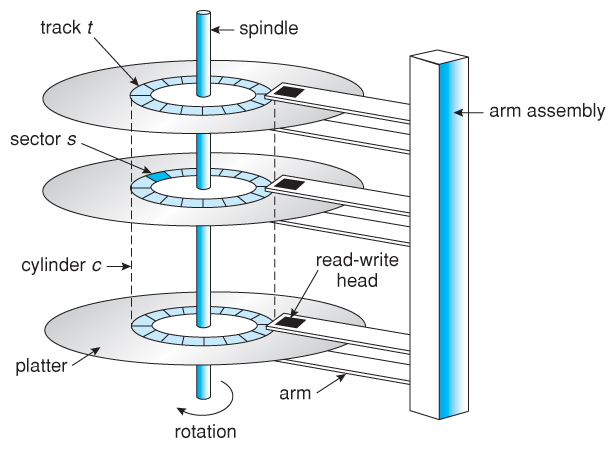

There are a few choices when it comes to disk. The classic disk we are used to is called a hard disk drive, or HDD. A HDD consists of a set of disks, each with its own disk head which can be used to read or write from the disk. When operating, all of the disks will spin quickly, and the disk heads will move across the disks to perform operations. Each disk in an HDD is split up into radial sections called sectors, where data is read and written only in sector-sized components. A few things fall out of this design. Firstly, reading sequentially from a HDD is much faster than reading randomly from an HDD. Reading sequentially only incurs one "seek", which can take milliseconds (an eternity for computers), whereas random reads incur a seek for each block of data read. Secondly, because we usually have multiple disks and disk heads, we have a few choices on how we want to split up our data among disk. Topics like disk striping and RAID redundancy are beyond the scope of this chapter, however. Lastly, while still much slower than volatile storage, HDDs are fast enough to be used in everyday computing, and so are equipped by many modern computers.

In the last decade or so, solid state drives or SSDs have become much more popular for consumer electronics. SSDs, unlike HDDs, are able to perform random reads and writes just as quickly as sequential reads and writes, as well as being in general much faster than HDDs. As a result, their popularity has ballooned and they have all but replaced HDDs. However, SSDs are a tad bit more expensive than HDDs, and they don't last quite as long. Indeed, an SSD can only be written to so many times before it breaks; in fact, one of the primary mechanisms that allows SSDs to work is one that remaps broken sectors to unbroken sectors. As sectors break throughout the lifetime of the SSD, your viable storage size will shrink, and the disk will slowly die. For short term consumer electronics or databases which are more read- than write-heavy, SSDs may be a great option.

Other forms of nonvolatile storage, like flash memory, exist, but aren't typically used for databases.

Volatile Storage

The other consequential category of storage is memory. Memory is volatile, which means that when power is lost, so is all of the data on memory. However, the tradeoff is that working directly with memory is both possible and quick, and is the primary workbench that your data will live on while it is being birthed, altered, and destroyed. There are two main kinds of random access memory (RAM): static RAM (SRAM) and dynamic RAM (DRAM). The former is faster but requires more energy than the second, which is slower but doesn't require a constant current necessarily. We will deal with how to manage memory in the rest of this chapter.

Processor Storage

At the tip top we have processor caches and registers. Reads and writes to these are blazingly fast, but the amount of storage here is predetermined by your processor vendor. Indeed, only a few kilobytes of cache and a few bytes of registers are available. At the compiler and operation level, these are used to make your programs run as quickly as possible, and they are too small to be of great concern to a database operator.

Storage Management

Now that we're aware of what storage kinds exist, we will learn of a few techniques we can use to manage it. In particular, given that we can only read or write in fixed-sized blocks, that we can only operate on data in memory, and that reading and writing from and to disk is expensive, we can design a system which maximizes speed while minimizing compute.

Pages

As we've said, in order to operate on data, we need to read it in from disk into memory, and in order to save it, we must write it back out to disk. Although we like to think of data in terms of bits and bytes, our disk and operating system handle data in units of pages. Formally, a page is the smallest amount of data that can be guaranteed to be written to disk in a single atomic operation, traditionally fixed at a uniform size, such as 4096 bytes. In other words, our operating system exclusively read from and write to disk in blocks of 4096 bytes. We can leverage this feature of our operating system to create a more organized and flexible storage scheme.

(It's worth noting that these days, multiple page sizes are supported on various architectures. Additionally, database systems are free to set their own page sizes to multiples of the underlying system's page size. However, these design choices come with various tradeoffs.)

Page Organization

Given a set of records, we have many potential strategies of storing them. One strategy is called a heap file, where the database is represented as a single, unorganized file, and records are inserted wherever there is space for it. However, heap files are not particularly organized. As you insert and delete data, especially if the data is not fixed-length, fragmentation in your file will lead to wasted space.

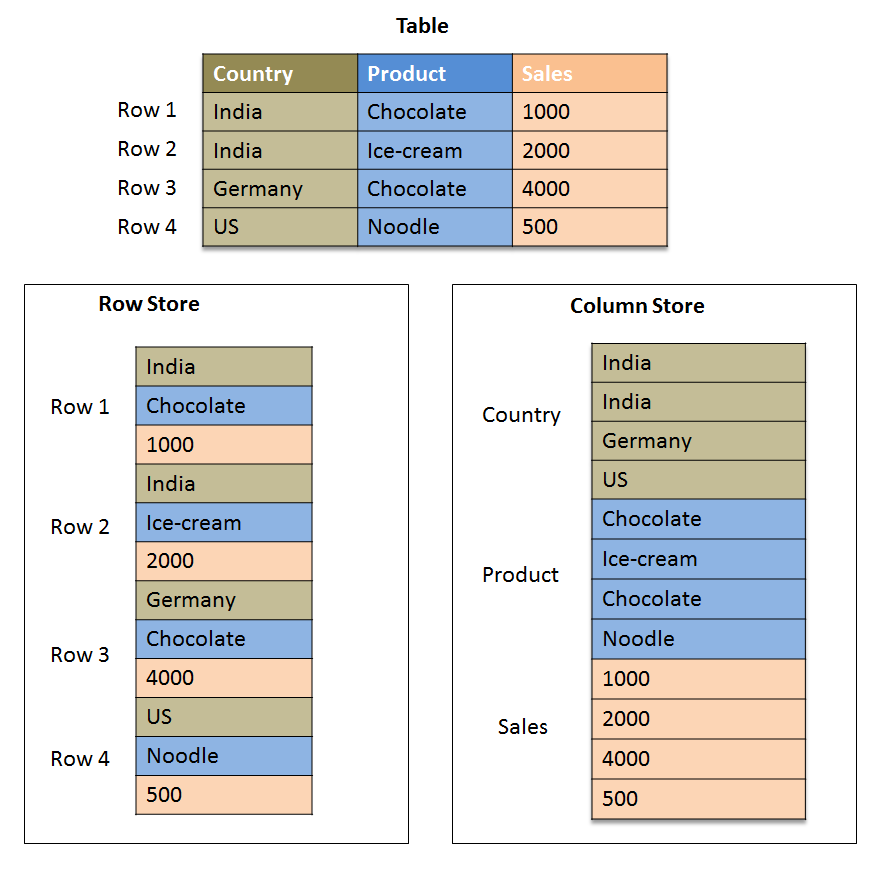

With fixed-length records, laying them out end-to-end in a page is not a bad idea. There are two canonical ways of doing this: in row-major order and in column-major order. In row-based systems, each record is stored in whole before the next. This allows us to access an entire record by only reading one page, and makes writing new records very easily. In column-based systems, all of the records' first field is stored first, then the second field, and so on. While this might seem ridiculous, if we only care about a certain field of a table (say, to calculate a metric), then with sequential reading, we can get all of the salient values much quicker. The former is much more common in OLTP-optimized systems, and the latter in OLAP-optimized systems. We can get the best of both worlds in a hybrid setup, where we store n instances of the first field, then n of the second field, and so on, before starting again with the first field. This allows us to benefit slightly from sequential reads while not fully giving up some niceness in quick tuple addition. As we will see later, storing tuples so that they are ordered on some field is incredibly useful for optimization purposes. Think about how each of these conventions affect the complexity of maintaining an order.

With variable-length records, our work is a bit harder. In particular, one huge loss, if implemented naively, is that we can no longer jump to a particular record in a page in constant time (before, we could have determined the position of entry N in page p by calculating (N % PAGE_SIZE) // TUPLE_LENGTH). How should we get past this? One method of storing variable-length records is using what are known as slotted pages.

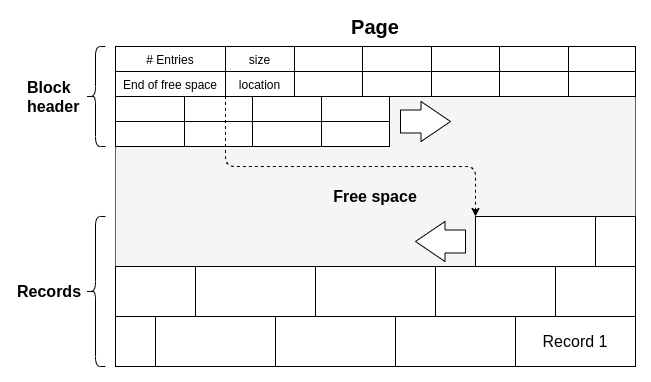

A slotted page works as follows. Each page is split up into three regions: a header and slotted region at the front, a data region at the back, and a free region in the middle. The header describes the basic metrics of the page, including how many items are in this page, where the header region ends, and where the data region begins.

When a new tuple is added, a fixed-size slot is created in the slotted region in the correct spot. The slotted region is what determines the order of the tuples; as we will see, the actual order of tuples may not correspond to the order of the slots. Each slot will contain the location of the actual tuple data in the page. This level of indirection makes our life easier in many ways. We can now access tuples in constant time by finding its offset in the slot. We can reorder slots without having to worry about reordering variable-length entries and dealing with fragmentation. There are a few drawbacks, however: some space is wasted for bookkeeping, and sequential reads are now somewhat tedious.

Page Table

Now that we've determined how records are stored in pages, it's up to us to use the pages!

It would be wasteful to read a page into memory and immediately write it out or throw it away if we've already gone through the trouble of reading a page in. After all, some pages are read very often, or might be read from or written to multiple times in a particular workload. We can delay evicting the page and writing it back out to memory until absolutely necessary, all while keeping the page around in case we need to use it again. This process is called caching.

Cached pages are stored in a buffer cache that we first pre-allocate, then fill. (The buffer must be page aligned, such that the data stored in a page-sized block is actually stored as a single page, and not sharded across two.) The buffer is represented as a series of N frames, each large enough to hold one page. When a page is brought into memory, it will reside in a frame. The number of frames N is typically tunable, but is not a large number.

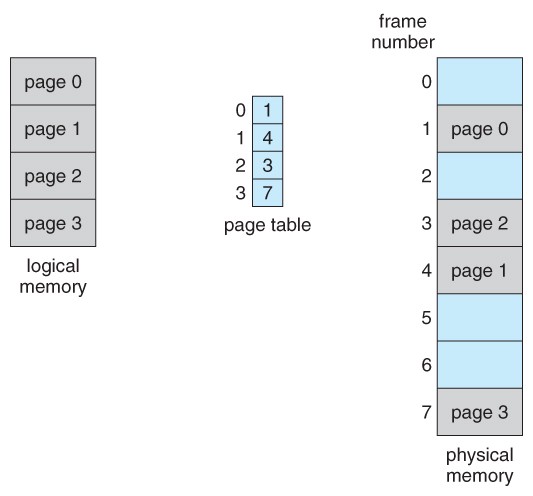

To keep track of which pages are in which frames, we have a page table. A page table is a map from page ids to frame ids, and indicates where pages are currently being stored in memory.

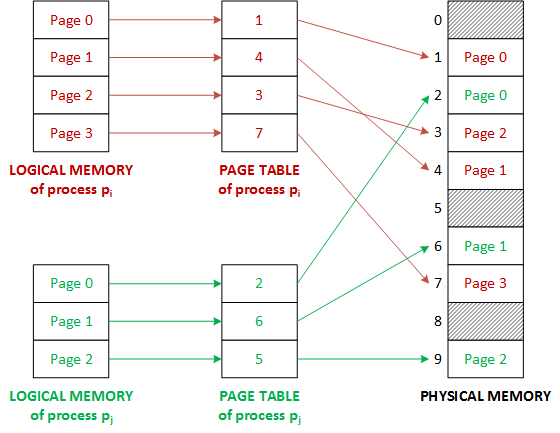

Let's consider an example. In the following diagram, our program has requested pages 0, 1, 2, and 3. To the external program, it seems as through these pages physically exist in order - this is known as the "logical memory" abstraction. The pages actually live in one of N frames that we've allocated. To figure out which frame each page lives in, we consult the page table, which maps the page ids to the frame its stored in. Later on, when this page table gets full, we will have to decide on a page to evict to make room for a new page.

Pinning Pages

While a page is in use, we want to make sure that it doesn't get evicted from the cache. Pinning a page marks it as in use and prevents it from being evicted. Pinning is usually implemented as a thread-safe counter of the number of threads currently using the page.

As an example, let's say we request a new page from the pager. Since this is a new page, we know that we're the only person using it, so we set the pin count to 1. Once we're finished, we decrement the pin count. If nobody else had taken the page in the meantime, we would be clear to free the page since the pin count would be 0. However, if someone else did take the page in the meantime, then the reference count would be greater than 0, meaning we cannot free the page.

Dirty Pages

While data persistence is good, reading from and writing to the disk are expensive operations. In order to minimize the amount of writes, we avoid writing data to the disk unless something has changed. Concretely, if a user only performs SELECTs, but does not INSERT, DELETE, or UPDATE entries on a particular page, then there is no need to flush the page to disk, since the page hasn't changed.

A page is considered dirty when it has been modified, and all dirty pages must be written out to disk before being evicted from the cache. This guarantees that we persist all changes we make to the database.

Getting and Evicting Pages

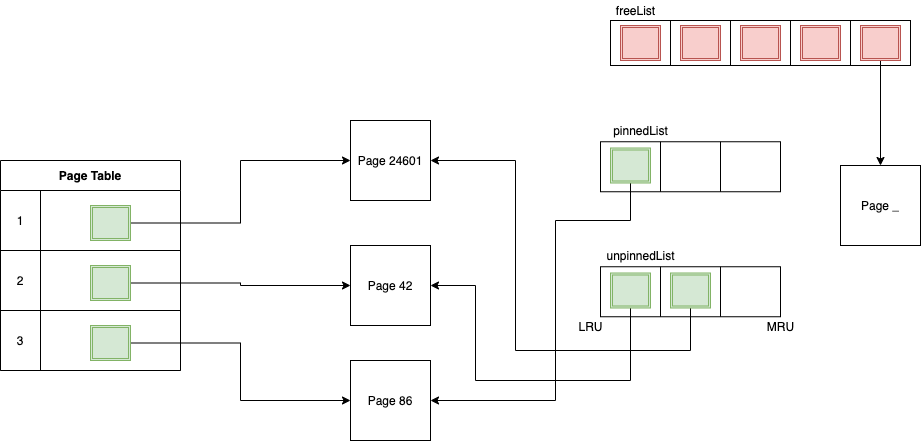

Whenever we get a page that is not already in our page table, we want to grab it from disk and keep track of it in our page table. The following is an example implementation of an eviction strategy. Initially, all of our empty frames are stored in a free list; while this free list is non-empty, we should be using one of our free frames to store new pages. However, once all of our frames are full, we should evict old pages from memory and use those newly freed frames to store our new pages.

In addition to the free list, we also keep track of a pinned list and an unpinned list. While a page is in use, it should be in the pinned list, and while it is not in use, it should be in the unpinned list. Critically, when a page shifts from being in use to not being in use (i.e. the pin count drops to 0), it should be removed from the pinned list and inserted into the end of the unpinned list. Symettrically, when a page shifts from being not in use to being in use (i.e. the pin count increases to 1 from 0), it should be removed from the unpinned list and inserted into the end of the pinned list. A page should never move to the free list (think about why). Make sure you're able to wrap your head around what these three lists are used for!

When a new page is requested and the free list is full, we need to evict an old page to create space. Notice that the first page in the unpinned list is most likely the best candidate to evict; it is not currently in use, and since we add new unpinned pages to the end of the unpinned list, it is the oldest such page. When we evict a page, we should write it out to disk if and only if the page was marked as dirty. We have actually implemented what is known as a least recently used cache, or an LRU cache. This is one of many possible caching strategies we could have used, but is simple and effective for most use cases. Thus, we evict this page and use that frame for our new page!

It's possible to have multiple pagers operating on the same allocated disk space. In the following example, each process thinks it has its own memory space when accessing the pages of a file. However, under the hood, the same amount of physical memory is still being used, but it is done in a way that is opaque to the user.